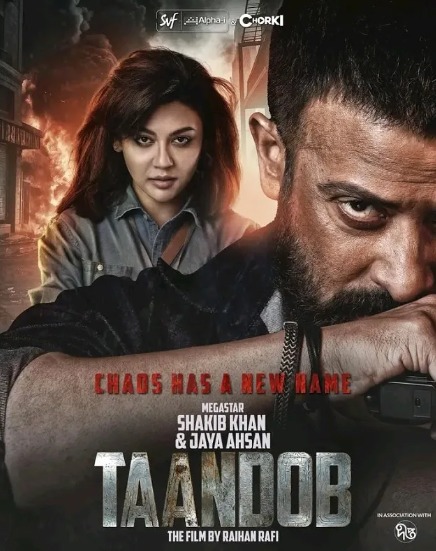

To watch Taandob (2025), directed by Raihan Rafi , is to experience narrative whiplash of the most calculated kind. The film is many things at once—hostage thriller, political drama, tragic romance, revenge saga, and media satire—layered over a genre-bending canvas that refuses linear comfort. At its most superficial, it’s an audacious action spectacle designed for mass appeal. But dig deeper, and what emerges is a searing, urgent interrogation of escapism—not as an indulgence, but as a radical necessity.

In a nation bruised by corruption, disappearances, unemployment, and media complicity, Rafi doesn’t just present escapism as refuge; he transforms it into resistance. He weaponizes genre itself to mirror a generation’s craving for meaning, release, and justice in a broken reality. Through a narrative that constantly flees from itself—only to circle back with renewed fury—Taandob insists that to survive in such a system, one must transcend it. Not through realism, but through the full-blown, operatic fantasy of vengeance, love, and spectacle.

From its opening frames, Taandob traps its characters—and the audience—inside the sterile, high-pressure environment of Channel Bangla, a private television newsroom taken hostage by a masked insurgent. What starts as a claustrophobic hostage thriller à la Dog Day Afternoon quickly mutates. Just when the audience begins to settle into the tension, Rafi yanks us backward into a prolonged, melancholic flashback detailing the tragic past of the supposed hostage-taker, Shadhin (Shakib Khan).

This flashback, which veers into territory more befitting a romantic social drama, is the film’s first major act of formal escapism. We are invited to view Shadhin not as a threat, but as a vulnerable, unemployed everyman—driven not by radical ideology, but by love and desperation. His doomed relationship with Nishat (Sabila Nur, heartbreakingly fragile) and his Kafkaesque descent into false accusations and police torture is framed not as aberration, but as systemic norm. In a society where the innocent are routinely sacrificed to protect the powerful, Rafi doesn’t build tension through plot—he builds grief through inevitability.

This whiplash continues throughout the film. A tragic romance becomes a prison-break thriller. A revenge saga becomes a media circus. Every time the story reaches an emotional or narrative breaking point, it splinters into a new genre. These ruptures aren’t random—they mirror the psychological fragmentation of a society numbed by trauma. Just as Shadhin/Mikhail seeks escape from torture, injustice, and memory, the film itself seeks formal escape from any container that might restrict its emotional or political ambition.

Nowhere is this more potent than in the now-infamous “Lichur Baganey” musical sequence—a Bollywood-esque song-and-dance number inserted at the height of the film’s darkest moment. To some viewers, it might appear incongruous, even offensive. But within the film’s logic, it’s a masterstroke. This isn’t escapism as denial; it’s escapism as exposure. The sequence collapses tone intentionally, forcing the audience to confront the absurdity of entertainment as national anesthetic. At the height of suffering, we dance—not because we’ve forgotten, but because it’s the only way to feel.

Rafi’s choreography of action and spectacle often veers into the surreal. Guns are fired in slow motion, bodies fall like dominoes, and Shakib Khan’s stoic rage becomes a performance within a performance, broadcast live to a nation. The film doesn’t hide its artificiality. On the contrary, it revels in it. Taandob isn’t about realism—it’s about catharsis. Like Greek tragedy or Shakespearean revenge plays, its goal is to externalize the unbearable. Through violence, song, flashback, and twist, the film builds a theater where truth must be performed because it will never be published.

The film’s boldest gambit comes late: the revelation that the man orchestrating the hostage crisis is not, in fact, Shadhin—but Mikhail, a wanted terrorist who has assumed his friend’s identity to avenge his death. This twist is both narrative and philosophical. The personal story of one wronged man becomes the mythic story of all wronged men. Mikhail ceases to be an individual; he becomes symbol—folk hero, martyr, ghost. In a society where institutions offer no recourse, justice must come from the dead returning in disguise.

This transformation speaks volumes about the psychological need for avatars in times of social decay. Taandob crafts its protagonist as a man who must erase himself to speak the truth. Identity becomes a costume. Truth becomes performance. The film posits that when systems fail, only myth can generate the emotional force necessary to produce change. Mikhail doesn’t just hijack a newsroom—he hijacks narrative itself.

Jaya Ahsan’s Saira, the investigative journalist turned co-conspirator, provides the film’s moral center. Her performance is a masterclass in composure under fire. Where Mikhail is raw emotion and vengeance, Saira is calculation and restraint. She represents the last shred of institutional idealism—the hope that journalism might still expose injustice. But when her own brother is forcibly disappeared and the media refuses to challenge state power, she chooses complicity over objectivity.

Her arc, like Mikhail’s, is one of radical escape. She escapes her profession’s ethical codes to finally confront the system that silenced her. Her quiet betrayal of journalistic norms is portrayed not as corruption, but as integrity in extremis. In a world where journalism cannot hold power to account, the only moral act may be to blow up the newsroom. Through Saira, the film issues a devastating critique of the Bangladeshi media: its cowardice, its collusion, and its impotence.

For Bangladeshi cinema, Taandob is not just a film—it’s a rupture. It takes topics often whispered—enforced disappearances, police torture, media censorship—and broadcasts them in a blockbuster register. The final scenes are pure revolutionary fantasy: a live-broadcast uprising, the collapse of elite power, and the tantalizing suggestion of a larger cinematic universe where justice might be serialized. This is where Rafi’s ambition reaches its most audacious peak. He refuses to let the film end in ambiguity or defeat. Instead, he offers something deeply unfashionable in serious cinema: hope.

That hope, however, is not naïve. It’s built on the understanding that reality will not fix itself. It must be exploded—then re-imagined. Taandob’s chaotic genre-bending, its tonal jolts, and its narrative excesses are all symptoms of a story too big for realism. Like V for Vendetta, Oldboy, or even Joker, Rafi’s film speaks in the fevered language of the unheard, the radicalized, and the disillusioned.

Of course, Taandob is not without flaws. Its screenplay is dense to the point of confusion. It leans heavily on exposition. Some of its tonal pivots will alienate traditional viewers, and its ambition sometimes outpaces its craft. But these are the flaws of a filmmaker swinging for the fences. Rafi is not trying to make a polished product—he’s trying to start a fire.

In doing so, he has made what may be the most important Bangladeshi commercial film in years. Not because it’s perfect, but because it dares to dream dangerously. It sees escapism not as the enemy of political cinema, but its missing weapon.

Taandob ends with the system burning—not in reality, but on screen. And yet, that illusion lingers. Because Rafi understands something vital: sometimes, the only way to make the powerful listen is to show them a world where they no longer exist.

In Taandob, escape is not cowardice. It is the first step toward revolution.

Abu Shahed Emon, Filmmaker