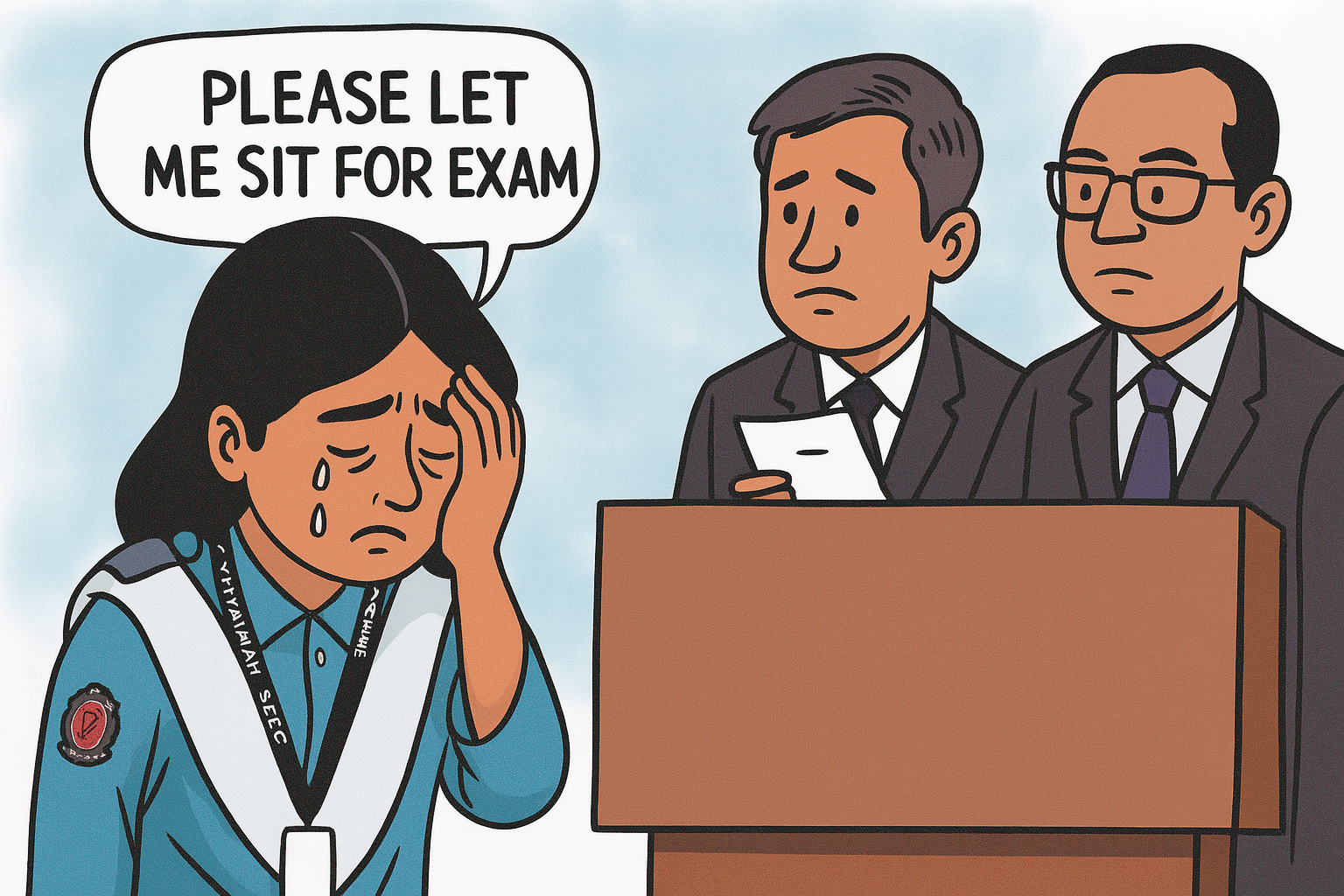

With highest empathy for Ayesha and her extra ordinary situation, almost all professional educator in their career face high ambivalence while taking decision relating to strict enforcement of rules relating to offering second chance in public examinations to latecomers who face kaleidoscopic situations.

In almost every country, public examinations — whether school board tests, university finals, or professional licensing exams — are subject to extremely strict rules. These rules exist for good reason: fairness, standardization, and, crucially, security. The idea is simple: everyone deserves a level playing field, and no candidate should have an advantage in accessing questions before others.

That is why late arrivals to examinations are almost universally treated harshly. Once an exam begins, its contents enter a vulnerable state: even a few minutes of unsupervised communication with someone outside could enable leaks. Therefore, most systems only allow a very limited grace period for late entry — typically 15 to 30 minutes — after which the doors close, and there is no comeback. If a student is locked out, the hard lesson is that punctuality is a pillar of exam integrity.

A Global Consensus

In the UK, exam boards like AQA or Cambridge strictly follow Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) procedures. Candidates may still be admitted within the first hour for GCSE or A-level exams, but after the “key time” — that is, the moment other candidates might have left — no entry is permitted. Re-sits are only available under exceptional circumstances, such as a terror attack or a certified family bereavement, and only through a formal appeal supported by “robust evidence.” During COVID-19, for example, JCQ allowed limited resits to address mass disruption, but never for ordinary lateness.

The United States operates along similar lines. SAT, GRE, and state bar exams all maintain strict security protocols. Once testing has begun, doors are shut, and no late entry is tolerated. Rescheduling is only available if the candidate can prove an extreme emergency, documented through hospital records or a police report. In 2023, California’s Bar Exam closed its doors to latecomers, upholding its strict rules to protect test integrity. Sometimes, as a gesture of fairness, test fees can be transferred to a later date if the student applies under extenuating circumstances, but the test slot itself is not automatically preserved.

Across continental Europe, policies echo this stance. From the French baccalauréat to Germany’s Abitur or Italy’s Maturità, missing the scheduled start time normally means forfeiting the chance to sit the paper. Only in force majeure situations — for instance, a verified transport strike or natural disaster — can an academic authority authorize a retake. A 2022 case in France is illustrative: a candidate who arrived 45 minutes late due to a train strike was initially barred from the exam but later granted a retake after an appeal, supported by official evidence. Another student, who simply overslept, was refused.

Why Such Rigid Rules?

Many people ask: why can’t there be an automatic “next-day” retake option? At first glance, this seems humane and practical. But legally and operationally, it raises enormous challenges. Once a question paper is administered, it becomes vulnerable to leaks. If a candidate misses the start time and then receives a promise to sit the same paper the next day, that student could easily collect the questions from others. In a world where social media can instantly spread information, this is a risk exam boards cannot afford.

Creating a brand new question paper for every latecomer is theoretically possible, but administratively nightmarish. Schools, universities, and professional testing agencies would face huge burdens: printing, transporting, securing, and marking multiple unique papers for every individual who shows up late. The potential for errors, unfairness, or unequal difficulty between versions would only grow.

Is There a Middle Path?

It is fair to argue that a rigid rule can sometimes punish those who suffer genuine, unforeseeable tragedy on exam day. This is why most countries already make allowances for documented emergencies, ranging from car crashes to sudden family deaths. But these exceptions are precisely defined and subject to formal verification. That is the key: independent, verifiable evidence that a candidate could not possibly have arrived on time through any reasonable means.

In short, the current system aims to balance compassion with the overriding need for exam fairness and security. If educational authorities did ever consider an “automatic next-day” arrangement, it would have to involve a new, highly controlled question set — a huge change in policy and resources.

Punctuality and personal responsibility remain fundamental to public examination systems around the world. While tragic and unexpected events will always merit humane consideration, there is no automatic entitlement to a retake simply for arriving late. Ultimately, public faith in the fairness of high-stakes testing depends on these tough, consistent rules. Arrive on time, and the system will be on your side; arrive too late, and the system must defend everyone’s right to a fair and secure exam.