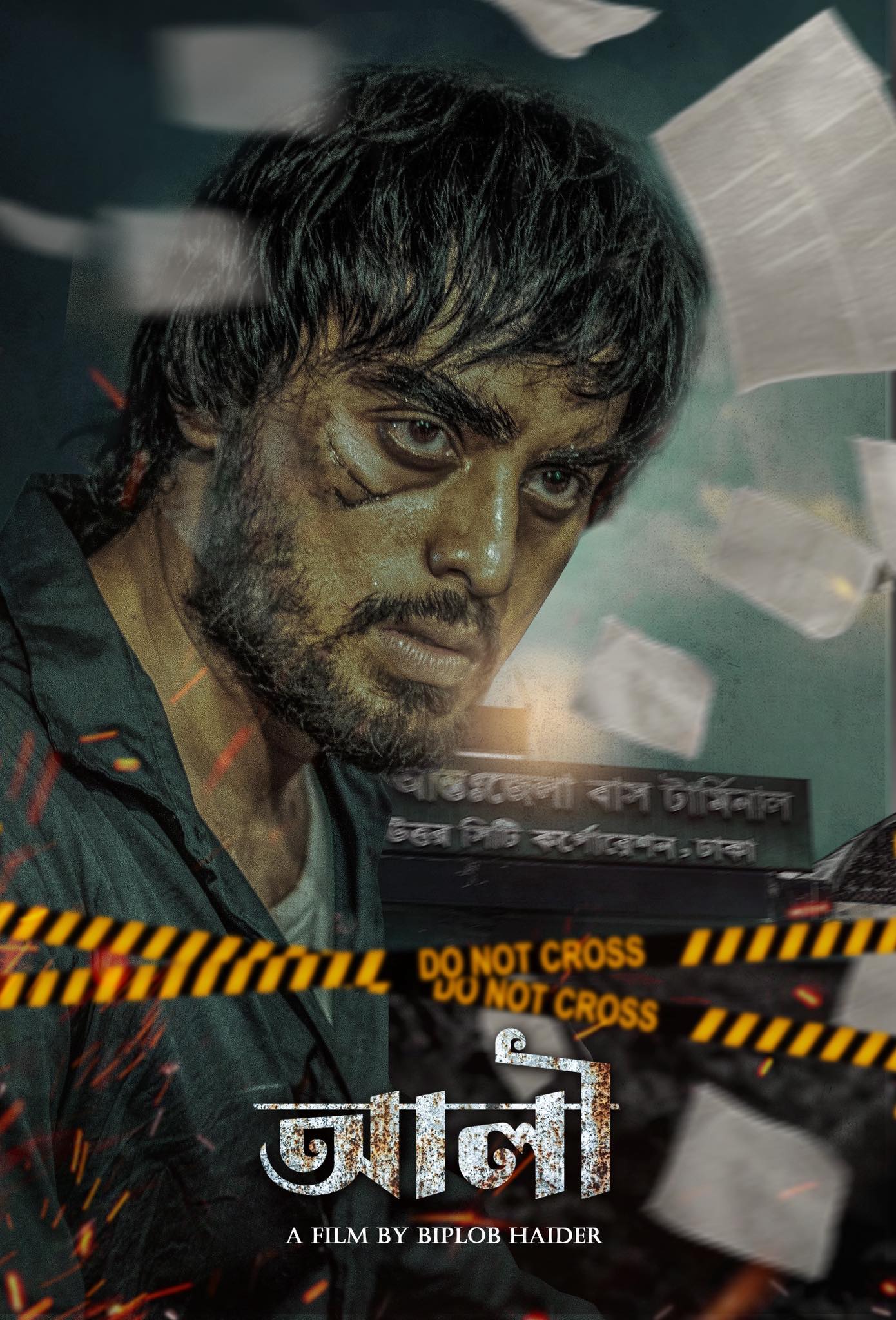

Ali (2025) opens with a disturbing yet symbolically charged sequence—a man being tortured, a girl feeding sugar to red ants, and a bold title card declaring: “Ali: Not Just a Name, But a Revolution.” With this jarring introduction, director Biplob Hayder hints at a politically infused, emotionally layered narrative. Unfortunately, what follows fails to fulfill that promise. Instead, the film descends into disjointed storytelling, excessive brutality, and tired tropes that render its emotional core inert.

The story begins with Roshni (Milita Mehzabin Orpa), a young woman kidnapped while peacefully enjoying a scenic view. What should have been a moment of rising tension quickly devolves into an unnecessarily detailed molestation scene. The film’s treatment of violence—particularly sexual violence—is not only gratuitous but disturbingly normalized. Rather than illuminating trauma or critiquing societal failure, it indulges in shock for the sake of drama. This is emblematic of a growing trend in mainstream Bangladeshi cinema, where violence is stylized and suffering sensationalized.

As if on cue, Ali (Irfan Sazzad)—Roshni’s mute and protective brother—appears from nowhere in a classic “commercial hero” fashion to rescue her. His entrance is heroic, yes, but wholly unearned in terms of cinematic build-up or realism. The film tries to root itself in the emotional bond between the siblings, but repeatedly undermines this with shallow plotting and uneven tone shifts.

We then transition into a domestic narrative: Roshni wishes to pursue higher education in Dhaka, a desire resisted by Ali. Eventually, he relents. Along the way, we are introduced to a “mean aunt,” sketched so thinly she becomes a caricature—her villainy established through a single line about cutting meals for her own child. These lazy shortcuts replace actual character development.

Roshni’s lover (played by Christian Tanmoy) soon enters the story, and a forced kiss attempt leads to a slap and a violent confrontation with Ali. But even this subplot feels like a checkmark on a screenplay outline rather than an organic narrative beat. The brother, persuaded once again, travels with Roshni to Dhaka. There, a hastily staged accident separates them, leading to a baffling flash-forward where Ali is seen in remand. The film spirals into a chaotic series of timelines, breaking narrative continuity and audience engagement alike.

From this point on, the film becomes a relentless barrage of contrived “chance encounters,” exaggerated villains, and implausible twists. Roshni is raped by her lover’s friend—again portrayed in disturbing detail—and this event becomes the catalyst for a revenge plot that feels more like genre pastiche than genuine reckoning. The film abandons its initial tone for melodrama, veering into courtroom theatrics that have no bearing on actual legal procedures.

The courtroom, in fact, becomes a stage for fantasy rather than justice. Judges cry. Lawyers (including a fleeting appearance by Misha Sawdagar) argue without evidence. Verdicts are delivered through emotion rather than logic. While cinematic liberty allows for dramatization, Ali misuses the courtroom setting to the point of absurdity—trivializing Roshni’s trauma and reducing justice to performance.

Irfan Sazzad is the film’s one constant. His portrayal of Ali—physically muted, emotionally expressive—is committed and sympathetic. Still, the overuse of a secondary character to translate his gestures, coupled with overly simplified mimicry of mute communication, detracts from what could have been a more dignified representation. Orpa, as Roshni, gives a sincere performance, but her character is often sidelined, becoming a vessel for male-driven vengeance rather than a subject of her own story.

Supporting roles suffer even worse fates. Shatabdi Wadud’s portrayal of a police officer is cartoonishly evil—an archetype dragged from outdated Bangla cinema. His sudden attempt to assault a humanitarian activist (played by Nomira Ahmed) is stopped by yet another chance encounter with Roshni’s lover, who appears just in time to beat him up—after which the antagonist simply vanishes from the plot. These narrative shortcuts not only insult the audience’s intelligence but also dilute the stakes.

Technically, the film has its strengths. Shohag Khan’s cinematography captures the natural beauty of the hills with a lyrical eye, and Jahid Nirob’s score, supported by Rubel (Flying Kites) on sound design, occasionally fills the emotional vacuum left by the screenplay. But no aesthetic can mask the exploitative nature of the film’s most violent scenes. Whether it’s rape, beatings, or revenge killings, these moments are treated with undue detail, making Ali a prime example of violence-as-spectacle in modern Bangladeshi commercial cinema.

In its ambition, Ali aims to tell a story of sacrifice, resilience, and justice. But in execution, it becomes an exhausting, often disturbing experience. The film’s reliance on randomness, undercooked subplots, and fantasy-laced legal drama transforms what could have been a poignant tale into a cautionary one—for filmmakers and audiences alike.

In the end, Ali (2025) is less a revolution than a regression. It serves as a stark reminder that emotional weight cannot be faked with slow-motion violence, and catharsis cannot come at the cost of coherence, compassion, or credibility.

Production Credits:

Directed by: Biplob Hayder. Produced by: Tajul Islam. Director of Photography: Shohag Khan. Edited by: Leon Rozario & Ashikur Rahman Sujon. Lyrics by: Pulok Anil. Songs & Music by: Jahid Nirob. BGM & Sound Design by: Rubel (Flying Kites). Costume Design by: Nabila Alam Polin. Art Direction by: Kamruzzaman Shumon. Prosthetic by: Khokon Mollah. Makeup by: Md Jonny. P

Abu Shahed Emon, Filmmaker