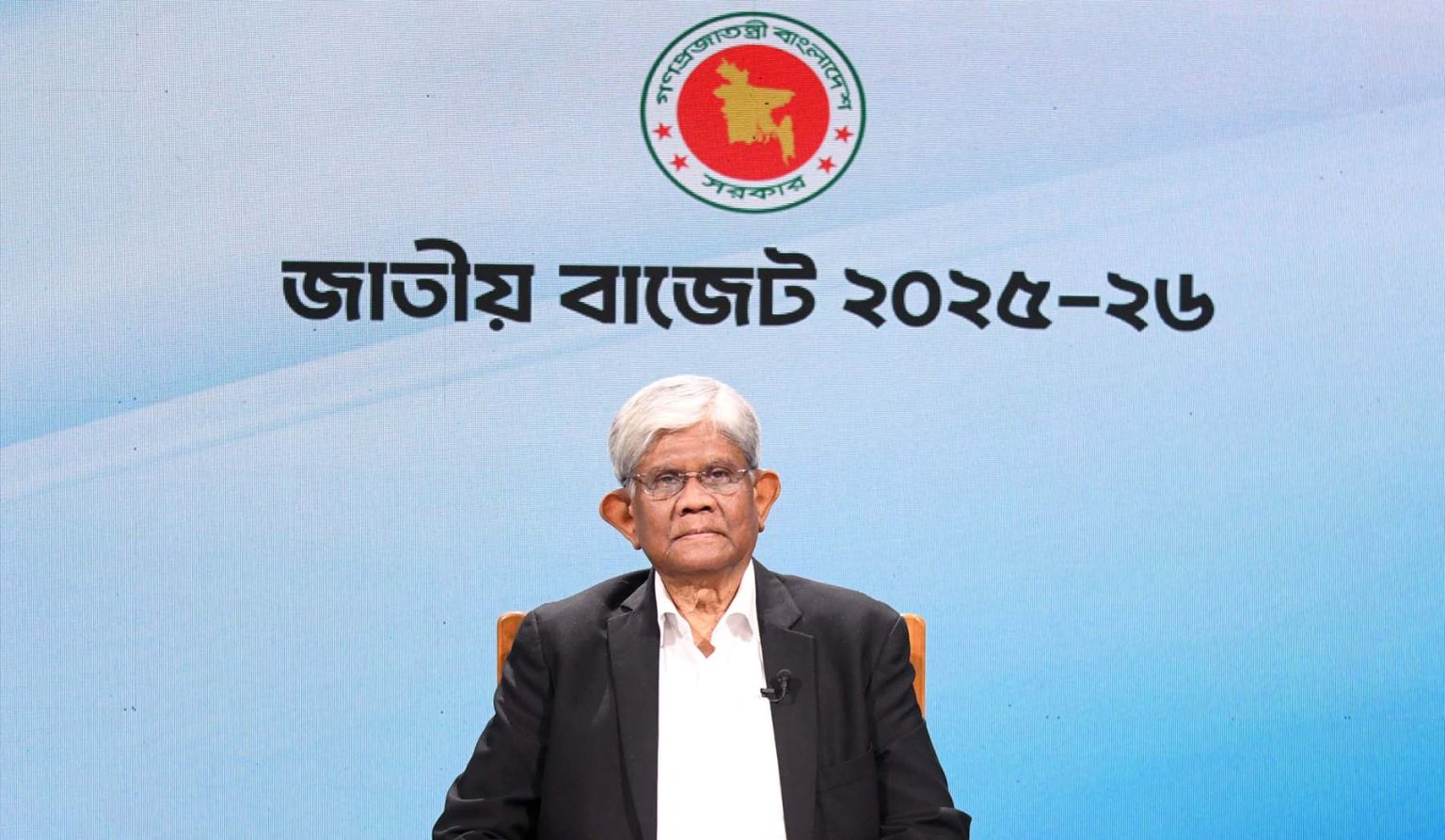

The budget for the 2025–26 fiscal year marked a historic departure from tradition—not just in content, but in form. For the first time in 17 years, the budget was placed outside of parliament, delivered through a pre-recorded televised speech by Finance Adviser Salehuddin Ahmed.

Lasting only 22 minutes, the broadcast stood in sharp contrast to the detailed, hours-long addresses typically delivered live in parliament by finance ministers, complete with opposition scrutiny and public debate.

Instead, this year’s presentation, stripped of political fanfare and framed in technocratic language, reflected both the transitional nature of the interim government and the delicate state of national governance.

The last time a budget was presented in this fashion was during the 2007–08 fiscal year under a previous caretaker administration.

With parliament inactive and national elections yet to be scheduled, this subdued rollout symbolised not just austerity in numbers, but also in democratic process.

What was perhaps even more remarkable than the format was the substance: for the first time in the country’s history, the government has proposed a smaller budget than the previous year.

The budget outlay for FY26 has been set at Tk 7.90 lakh crore, 0.9% less than the Tk 7.97 lakh crore proposed last year. It also represents just 12.65% of gross domestic product—the lowest budget-to-GDP ratio since FY11.

“This year’s budget is somewhat exceptional,” said Salehuddin in his televised speech. “We are proposing a smaller budget… Moving away from a growth-centric concept, we have tried to emphasise the concept of holistic development.”

He stressed a shift in priorities from traditional infrastructure to human development, focusing on education, health, employment, governance, and equity. “Our goal is to build a society free of poverty, unemployment, and carbon dependency—a society where inequality has no place.”

However, critics argue that while the tone was inclusive, the policy roadmap remained vague. After months of stabilising what many economists described as a “listing economic ship,” the interim government has undoubtedly delivered a cautious and technically sound budget.

But it fails where it matters most: delivering relief to ordinary citizens and charting a path to long-term recovery, they added.

The adviser’s anti-discrimination rhetoric, while admirable, is undercut by a revenue strategy that tightens the screws on households already strained by inflation, which has hovered near 10% for the past three years.

In line with IMF conditions tied to its $4.7 billion loan programme, the government has targeted a 9% tax-to-GDP ratio, driven by hikes in VAT, the removal of exemptions, and higher advance taxes on imports and vehicles. The result? A likely increase in the cost of essentials—from LPG cylinders and LED bulbs to electronics and building materials—while only a few necessities, like iodised salt and liquid milk, receive minor relief.

“Tax fairness must be ensured. Expanding the tax base, not burdening the existing taxpayers, is the way forward,” warned Ahsan Khan Chowdhury, CEO of PRAN-RFL Group, while speaking to an English daily.

Salehuddin, however, defended the direction: “We are rationalising tax exemptions and automating tax collection systems to increase efficiency and transparency.”

Yet the numbers show an economy still gasping for growth. GDP growth has slumped to 3.97%, private sector credit growth has hit a record low, and investment-to-GDP has fallen to 29.38%—the weakest in a decade.

The budget projects 5.5% growth in FY26, but institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank remain unconvinced, predicting sub-5% outcomes.

Meanwhile, the job market paints a grim picture. Over 60,000 jobs have been lost in the past nine months. Service sector employment is down 2.6%, industrial jobs have declined by 0.8%, and three in five households are now relying on savings or debt to make ends meet.

“Inflation control came at a cost,” Salehuddin admitted. “But had we not taken these hard decisions, the crisis would have deepened.”

Even so, the most pressing concern for many economists is the absence of a credible recovery roadmap, especially regarding private investment. Foreign direct investment is falling, and domestic business sentiment remains paralysed by energy shortages, legal unpredictability, and political uncertainty.

“I don’t need promises—I need gas,” said Khorshed Alam, managing director of Little Star Spinning Mills, voicing a frustration echoed across the industrial sector.

The budget includes vague promises to review power purchase agreements and reduce energy production costs by 10%, but there is no concrete plan for energy security.

With a trimmed Annual Development Programme (ADP) and high public borrowing, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) also fear being crowded out of already tight credit markets.

The budget deficit is projected at Tk 2.26 lakh crore, or 3.62% of GDP—down from 3.87% in the previous year. Officials at the finance ministry say the fiscal consolidation strategy aims to make the budget more implementable.

But austerity without reform, many warn, is not a growth strategy. “Too much austerity in a fragile economy risks a collapse in demand,” Fahmida Khatun of the Centre for Policy Dialogue told a media outlet.

To the interim government’s credit, foreign reserves have stabilised above $20 billion, remittances and exports have seen modest growth, and Bangladesh Bank has begun reining in rogue lenders.

Still, Salehuddin conceded in his speech: “Inflation has not been fully brought under control. External shocks and internal uncertainty continue to pose risks.”

With elections still unscheduled and LDC graduation looming in 2026, the window for meaningful structural reform is narrowing.

The FY26 budget reflects a clear break from past recklessness, but it lacks a growth engine, a comprehensive reform agenda, and a social contract that connects the budget’s priorities to the lived reality of the people.

Bangladesh needed a visionary fiscal plan. What it received was a cautious one—carefully balanced for stability, but hollow on strategy. Whether the country can move from stabilisation to genuine transformation remains the defining question of its economic future.