In the narrow corridor of a private hospital in Dhaka, Rajon Biswas wipes sweat off his forehead as he clutches a prescription for his elderly father, Prashanta Biswas, who sits silently beside him, staring at a wall.

“The operation in Kolkata was scheduled for early April. Everything was set. We just didn’t get the visa,” Rajon says with frustration. “We tried five different places in Dhaka, but nothing worked. Now, the same procedure here costs almost twice as much.”

Scenes like this are no longer rare. From Dhaka to Bogura, from Narail to Rangpur—thousands of critically ill patients, who once sought treatment in India, are now stuck in limbo at home as they fell victim to a recent tightening of Indian medical visa rules.

The hospitals are overwhelmed. Queues stretch long. The uncertainty is stifling.

Rokeya Begum, who travelled from Bogura with her ailing husband, has been waiting three weeks for a confirmed surgery date.

“If we could’ve gone to India, he’d be resting after surgery by now,” she says, her voice weary. In Narail, Mizanur Rahman still carries a prescription from Apollo Hospital, Chennai, along with some unused Indian rupees.

“Everything was ready—except the visa. Now even getting a surgery slot in Dhaka is a battle.”

The pressure on the country’s healthcare system is mounting.

Data from the National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases (NICVD) show over the past three months, the hospital’s outpatient department has treated an average of 1,800 patients per day—nearly 30% higher than normal.

The number of patients on the waiting list for surgery has jumped to 1,650, compared to the usual figure of under 1,200.

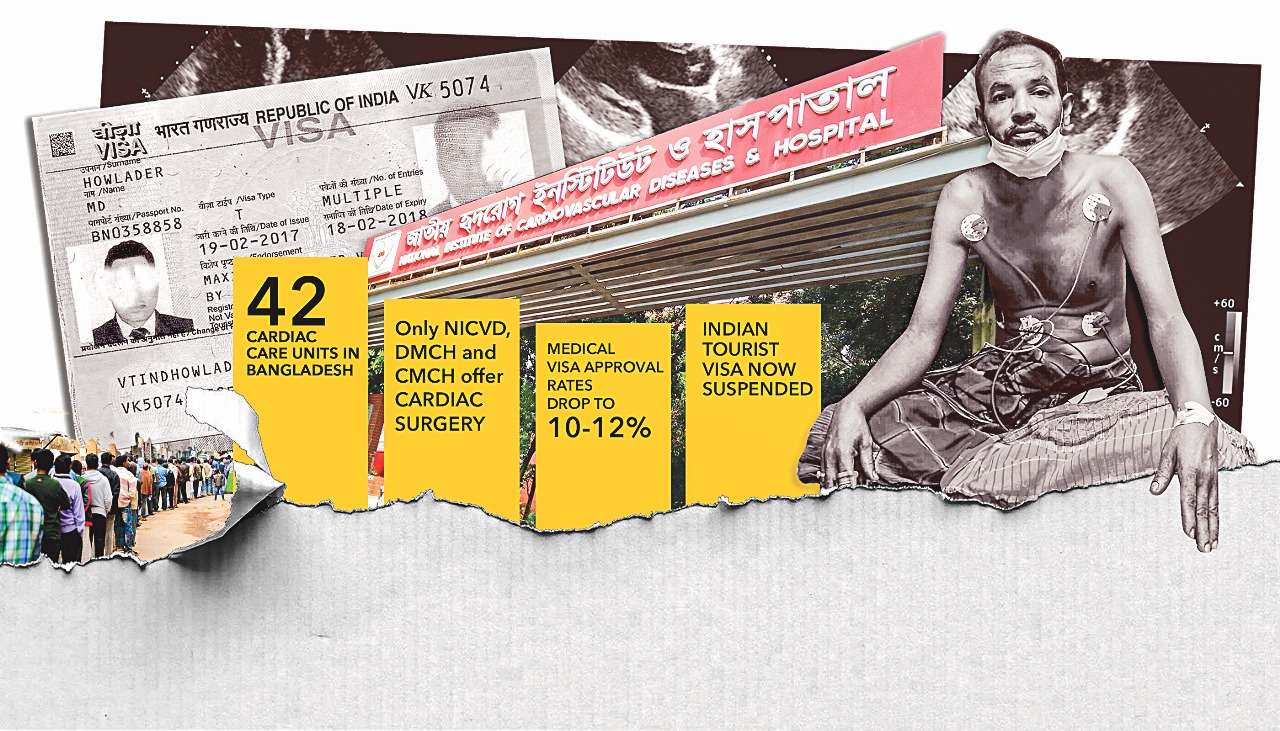

Officials from private visa processing agencies in Baridhara and Mohammadpur say the numbers speak for themselves. “We used to process several thousand Indian visas per month,” said one official. “Now we barely manage 200. Medical visa approval rates have dropped to just 10–12%.”

Applicants are now required to submit extra documentation directly to the Indian High Commission, which verifies medical urgency before issuing visas. Tourist visas, meanwhile, remain largely suspended.

India is regularly issuing visas to Bangladeshi nationals for various reasons, the country’s foreign ministry spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal said on Thursday.

Speaking at the weekly press briefing, he stated, “We are issuing visas—many visas—for different categories, including medical emergencies and student travel.”

However, he admitted that he did not have the exact figures regarding how many visas had been granted to Bangladeshis in recent months.

The country’s existing healthcare infrastructure is not equipped to absorb this sudden influx.

According to the Cardiac Surgeon Society of Bangladesh, there are 42 cardiac care units nationwide, but only 32 have full surgical capabilities. Among government facilities, only NICVD, Dhaka Medical College, and Chattogram Medical College offer cardiac surgery.

In other major cities like Khulna, Rangpur, and Sylhet, only diagnostic procedures such as angiograms are available—no surgeries.

The shortage extends to cath labs as well, which are essential for procedures like angioplasty and pacemaker implants. Of the 87 cath labs in Bangladesh, eight remain non-functional. NICVD alone has three out-of-order machines.

Other public hospitals, including the Dhaka Shishu Hospital and several divisional medical colleges, lack trained staff to operate existing equipment.

Government-run hospitals that offer stents in blocked arteries are available in only eight medical colleges. A plan to establish specialised hospitals in all eight divisions was launched in 2019 but has yet to materialise.

The project deadline has been extended to 2025, but progress remains slow.

“Treatment facilities outside Dhaka are available, but they are far from sufficient,” said Prof Dr Wadud Chowdhury, Director of NICVD. “Everyone ends up coming to Dhaka. We have 1,250 beds, but 1,500 to 1,800 patients are admitted on average each day.”

Private hospitals are seeing a similar surge. Hospitals like United, LabAid, Apollo, and Ibn Sina are all experiencing longer waiting lists and rising costs. For major surgeries, patients now have to wait more than a month.

Dr Ahmad Parvez Zabeen, a public-health expert, believes the current crisis reflects a structural flaw. “Our entire health system is Dhaka-centric. We must decentralise. Without reforming healthcare policy and investing in regional infrastructure, this dependence on foreign treatment will continue—and become increasingly unsustainable.”

In response, the Ministry of Health says it is prioritising medical decentralisation. “We are actively working to improve healthcare services outside Dhaka,” a ministry spokesperson stated.

But for Rajon, Rokeya and Mizanur, reality remains unchanged. They wait—sometimes days, sometimes weeks—outside crowded hospital wings.