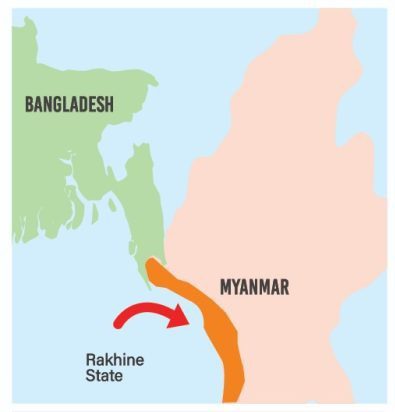

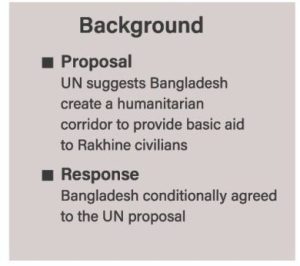

Along the shallow waters of the Naf River, running between Teknaf and Maungdaw, two contrasting narratives are carried by the northern winds. On one side lies the optimistic portrayal of a proposed “humanitarian corridor”—as recently highlighted by United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres—to deliver vital aid to crisis-stricken Rakhine. On the other hand, rising concerns on social media and within certain political circles warn: could this initiative inadvertently open a backdoor to a wider proxy conflict? The debate reached such intensity that the Press Secretary to the Chief Advisor’s Office felt compelled to address the issue personally on social media. According to his statement, “The Government of Bangladesh has entered into no formal agreement with the UN or any other entity regarding a ‘humanitarian corridor’; it has merely expressed readiness to offer logistical support if required.” This firm denial dispelled a cloud of speculation but simultaneously invited deeper reflection on Bangladesh’s diplomacy, security, and humanitarian obligations surrounding the Rakhine crisis.

Diplomatic context: Dhaka’s ‘low-profile activism’

Today, Rakhine is a veritable powder keg. Fierce battles between Myanmar’s military junta and the Arakan Army (AA), the violent rivalry between ARSA and RSO, and the unrelenting narcotics trade have transformed the region into a volatile cauldron. Against this backdrop, the UN’s proposal—to use a combined naval and land route via Teknaf and Ghumdhum for aid delivery—appears logical on the global stage. However, Dhaka is acutely aware that amidst the moist Naf River breezes, weapons fragments and yaba fumes often accompany aid convoys. Past experience, especially post-2017, demonstrated that yaba networks, controlled by ARSA and RSO, spread from Cox’s Bazar camps into Narayanganj, Dhaka, and Hathazari. The recent arrest of ARSA leader Ataullah Jununi by RAB-11 in Narayanganj only the resilience of these networks. Thus, while Bangladesh maintains an open-door diplomacy regarding international cooperation, it has, to date, refrained from signing any formal corridor agreements.

Government clarifications vs. disinformation

The Press Secretary’s statement clarified three essential points:

First, Bangladesh’s role is that of a “facilitating neighbour”—it may open supply routes, but the ownership and distribution of aid would remain with the United Nations.

Second, no definitive decision has been finalised; comprehensive consultations with all domestic stakeholders—including ministries, Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB), and local administration—are still pending.

Third, the notion of a “major power’s geopolitical strategy” leveraging Bangladesh is merely baseless rumour.

The trend of disinformation cannot be ignored. Over the past months, online portals have floated notions of a Chinese “Mandarin Corridor” or a “Washington-sponsored relief passage.” However, media fact-checks have clarified that no major power has yet established operational infrastructure in Rakhine; the UN’s current emergency funds remain strictly confined to food and healthcare aid.

Shadows of ARSA-RSO and narcotics

Nevertheless, concerns are not unfounded, given the grim reality of border syndicates. ARSA and RSO maintain considerable influence within Cox’s Bazar refugee camps. In FY 2024–25 alone, BGB seized over 17 million yaba tablets, most of them trafficked across the Naf River. As the junta-AA war drags on, the risk of looted Chinese CQ-A rifles, PF-98 rocket launchers, or M22 assault rifles leaking into the black market rises. Even a fraction of these weapons could dangerously empower ARSA and RSO. Therefore, unless scanners, digital seals, and geo-fence monitoring systems accurately detect high-risk cargo, the corridor risks becoming a lucrative “golden route” for traffickers.

The Arakan Army’s ‘goodwill’ and proxy crosswinds

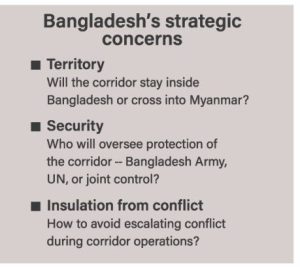

The Arakan Army portrays itself as the defender of ethnic Rakhine rights. Recent incidents—such as the handover of Bangladeshi fishermen to BGB—are described by the AA as “goodwill gestures.” However, the AA also acknowledges that an operational corridor would offer them rear logistic coverage. Under China’s Kyaukphyu Megaproject, the AA is a de facto security partner, while India’s Kaladan Multimodal Project further complicates matters, as Delhi hesitates to alienate the AA entirely. In this intricate triangle, should Dhaka formally sign a corridor agreement, the shadows of international polarisation would loom large—precisely the nucleus of proxy war concerns.

Security preparations: BGB’s ‘three-layer air wall’

The Government’s stance is firm: regardless of diplomatic decisions, border security will not be compromised. BGB has already installed solar-powered surveillance towers, mini radars, and drone-jammers along the Ghumdhum-Thangkhali-Reju alignment. Indian media outlets claim that a light infantry company from the Bangladesh Army stands ready as a supporting unit. Gantry scanners and mobile van-scanners will gamma-scan every convoy truck; any breach of the digital seals will trigger immediate geo-fence alerts. Bangladesh authorities are also likely to mandate ISO-style arms-residue testing and canine sweeps every six months.

Humanitarian imperatives and Dhaka’s ‘conditional approach’

From a humanitarian perspective, the need for a corridor is undeniable. UN data shows that over 200,000 people have been displaced in Rakhine within the first quarter of 2025 alone, with severe food shortages looming. Dhaka fears that an unchecked humanitarian disaster could trigger another refugee influx, overwhelming already saturated camps sheltering over nine hundred thousand Rohingya. Hence, Bangladesh asserts: “Let there be aid, but ensure measurable progress on repatriation.” Leveraging Malaysia’s upcoming ASEAN Chairmanship, Dhaka is advocating for a “Corridor Plus Repatriation” package, ensuring that every wheel carrying aid also symbolically carries Bangladesh’s sovereign right to facilitate the Rohingyas’ dignified return.

Risks are real, but rumours are not

In summary, since no binding agreement has yet been signed, the idea that a “major power is dragging Bangladesh into a proxy war” remains speculative at best. However, the risks posed by arms-trafficking syndicates, ARSA-RSO recruitment, AA’s potential logistics piggybacking, and covert commercial circuits are very real. These risks can be mitigated—if Dhaka rigorously enforces its announced conditional model.

Real questions

The real questions are thus twofold. First—could the Rakhine aid corridor ultimately entangle Dhaka from a “neutral facilitator” into an unwitting “partisan proxy”? Official documents thus far suggest otherwise. Second—can Bangladesh morally or diplomatically turn away from the humanitarian suffering unfolding just across the Naf? The burden is both ethical and strategic.

If ever realised, the Teknaf-Maungdaw Corridor will stand atop a fragile bridge of armed neutrality—where every scanner’s flicker, every contractual clause, and every police-firstline response will determine whether the passage saves lives or instead, sows the seeds for new cross-border instability.

The answer remains open. But the Government’s current message is unambiguous: Bangladesh will stand by humanitarian principles—but will not allow its sovereign security to become a test case.

The writer is a poet and journalist