Ten months after the fall of the Sheikh Hasina government, Obaidul Quader has broken his silence in a rare interview—recounting his harrowing escape from death on August 5.

“I was very lucky. I wasn’t supposed to survive that day. Death came very close – right in my own area of the parliament,” he told Indian media outlet The Wall, referring to the situation after Sheikh Hasina had flown to India.

In the 23-minute, 51-second interview with The Wall’s Executive Editor Amal Sarkar, the Awami League general secretary revealed that this was the first time he was sharing his August 5 experience with any media outlet.

He recounted how he took shelter in a nearby house in the parliament area. Protesters and mobs were surging from all sides, originally targeting the nearby prime minister’s residence.

“We were shocked when the protest spilled into the parliament area. There were scenes of looting, mob-style chaos. Many of the people didn’t even seem politically motivated—it was more like an uprising of looters,” he claimed.

The mob also attacked the house where Quader had taken shelter, unaware he was inside. “They ransacked my home. But I didn’t expect them to storm the house I had taken refuge in. They did, and began smashing things and looting there too,” he said.

Quader recounted hiding in a bathroom with his wife for nearly five hours. “They were even looting the commodes and basins. My wife kept saying I (Quader) was sick to deter them from entering.”

“At one point, they threatened to break in. My wife asked what to do. I said—open the door. Let whatever happens, happen.”

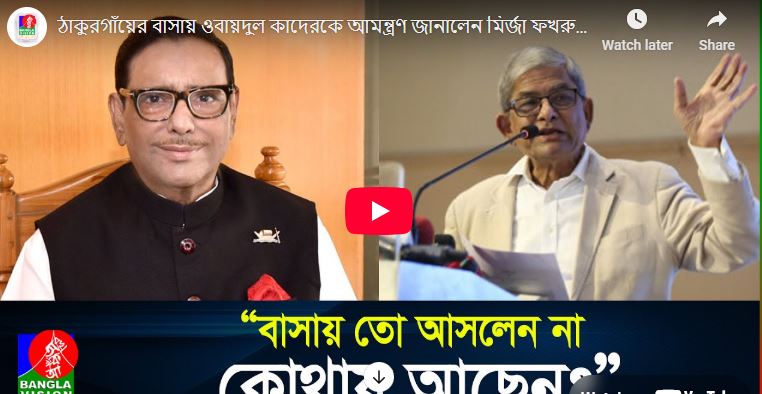

As a minister and general secretary of the Awami League, activities of which are now banned, Quader had earlier joked: “We won’t run away. If needed, we’ll stay at Mirza Fakhrul’s house.” After the regime change, BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir publicly responded, “Where is Mr Quader now? Come to my house, my area.”

But in reality, Quader in the interview described what happened next: “Seven or eight young men entered with aggressive attitudes. One looked at me and asked—your leader (Hasina) has fled, why didn’t you? I said nothing.”

Then, surprisingly, their demeanour shifted. “They started taking selfies with me. Some of them recognised me. Their aggression suddenly cooled. But then a debate began—some wanted to hand me over to the army, others to the mob.”

He said the group disguised him with a mask, badge, and flag, and walked him and his wife toward the main road near Ganobhaban. A random empty—an auto-rickshaw, in fact—appeared.

“Maybe it was fate,” Quader said. They got in, and the men told people along the road, “Uncle is here, Auntie is sick—taking them to hospital. Don’t disturb.”

Reflecting on that moment, Quader said, “I never thought I would survive when they entered that bathroom. It was pure luck—completely unexpected.”

He acknowledged what could have happened: “Those boys could’ve handed me to the army. There were opposition people on the streets. I could’ve been killed.”

After escaping, he stayed in Bangladesh for nearly three months trying to reorganise, connecting with garment workers and dissatisfied groups. But eventually, arrests began. “I was next after the leader (Hasina). I was accused in 212 murder cases. Requests came from here (India) for me to leave cautiously.”

Quader, last seen publicly on August 3, 2024, at the AL Dhanmondi office, became a viral topic after he said, “Who are they, where did they come from?”—a comment that spread widely on social media.