With the 10-month-old interim government preparing to unveil its first national budget in the absence of a functioning parliament, Bangladesh finds itself at a precarious economic juncture.

Stubborn inflation, dwindling investor confidence, rising unemployment, and unresolved questions about political legitimacy have created a fraught backdrop.

Finance Adviser Salehuddin Ahmed will present the Tk 7.9 lakh crore budget for FY26 on Monday, broadcast live on television and radio. Analysts argue this budget must be more than an accounting exercise—it must offer a credible path to economic stabilisation, structural reform, and public trust.

Sluggish growth

Provisional data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) shows FY25 recorded the country’s lowest GDP growth since the Covid-19 pandemic—just 3.97%.

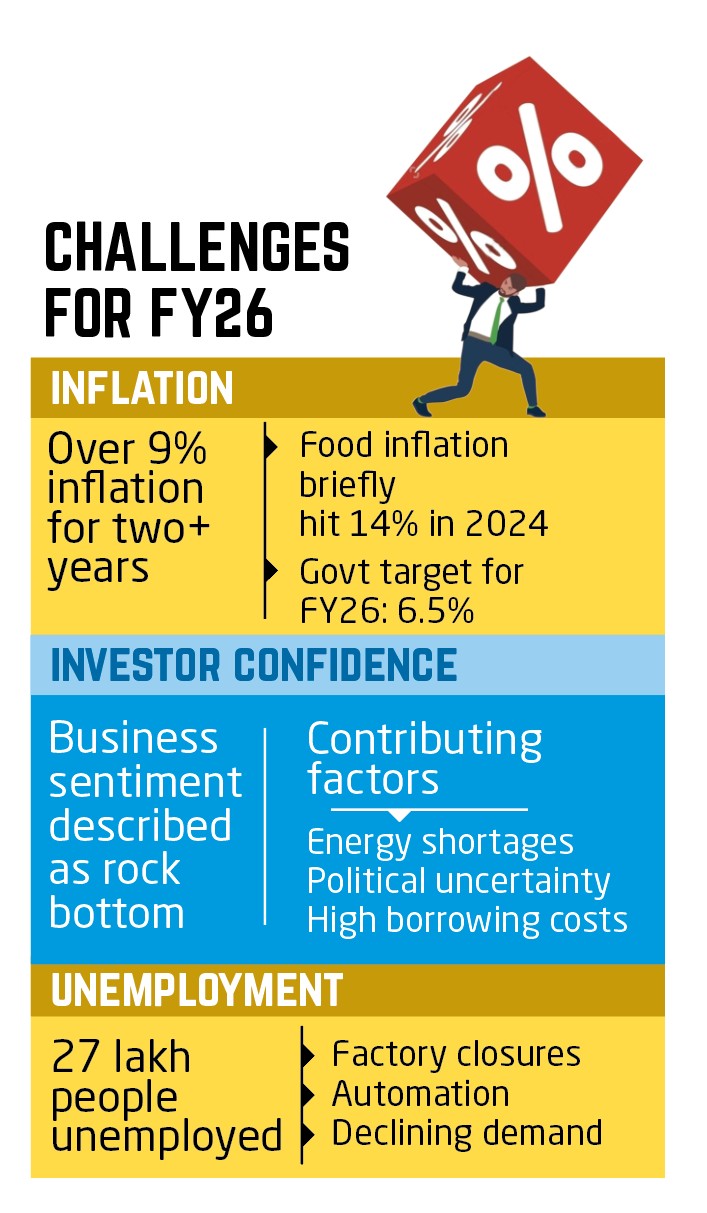

The slowdown is widespread: 27 lakh people are officially unemployed, labour force participation has declined, imports have fallen, and private investment has nearly stalled. Persistently high interest rates are exacerbating the downturn.

Economists argue the situation requires more than routine fiscal planning. This year’s budget must act as a blueprint for recovery amid both economic and institutional fragility.

Inflation erodes livelihoods

Inflation remains the most pressing concern. Consumer prices have stayed above 9% for over two years, with food inflation briefly crossing 14% in 2024. Essentials such as rice, lentils, oil, and protein-rich foods have become unaffordable for many households.

“The middle class is shrinking. The poor are slipping into extreme poverty. It’s no longer just an economic issue—it’s a humanitarian one,” said economist Hossain Zillur Rahman.

The interim government—installed after the Sheikh Hasina-led regime was ousted in a mass uprising last August—has promised to bring inflation down to 6.5% in FY26. Experts are skeptical.

“It will take more than just monetary tightening,” said Fahmida Khatun, executive director of the Centre for Policy Dialogue. She pointed to supply-side constraints, import delays, and weak market oversight as core issues. She called for targeted food and energy subsidies, improved logistics, and increased investment in domestic agriculture.

Investment sentiment at ‘rock bottom’

If inflation is the fire, investor anxiety is the smoke that continues to cloud the outlook. Business sentiment remains grim, hampered by energy shortages, political uncertainty, and high borrowing costs.

Syed Mahbubur Rahman, CEO of Mutual Trust Bank, described the investment climate as at “rock bottom.” Confidence in law and order and regulatory predictability has eroded, he noted.

Private sector credit growth was only 7% in early 2025—the lowest in a decade. Capital machinery imports dropped 23% in the first nine months of FY25, raising concerns over long-term production capacity. Economist Sadiq Ahmed of the Policy Research Institute called this a “red flag.”

The government’s growing reliance on domestic borrowing is also crowding out private investment. Interest payments now consume 22% of the total revenue budget, reducing fiscal space for development spending.

Jobs crisis and shrinking private sector

The private sector, which employs around 95% of the workforce, is under severe strain. The Bangladesh Employers’ Federation (BEF) estimates that automation, factory closures, and downsizing have quietly reduced the workforce by 3–5% over the past two years.

“We’re witnessing a silent employment crisis,” Farooq Ahmed, BEF secretary general, told an English day. “Hiring has frozen. Many firms are cutting staff just to survive.”

Even high-performing sectors like garments and IT are struggling. The RMG industry has lost over 62,000 jobs, while software firms have laid off about 20% of engineers due to stalled government procurement and declining domestic demand.

“This isn’t a cyclical issue—it’s structural,” economist Selim Raihan was quoted by a newspaper recently. He emphasised urgent reforms in energy, trade policy, and regulatory certainty to rebuild business confidence.

Fiscal prudence or austerity?

The FY26 budget is expected to total Tk 7.9 lakh crore—0.87% smaller than FY25’s original plan. The Annual Development Programme (ADP) is set to shrink to Tk 2.3 lakh crore, while the revenue budget will rise to Tk 5.6 lakh crore.

“There will be no new mega projects. We’re prioritising energy, education, agriculture, and health,” said Finance Adviser Ahmed. However, allocations suggest a different focus: education and health are expected to receive just 20% of the development budget, while transport and infrastructure will take 26%.

“This reflects a continued bias towards physical infrastructure over human development,” said economist Selim Jahan.

According to officials at the planning ministry, the size of the ADP has been reduced due to historically low implementation in the outgoing fiscal year.

In the first 10 months of FY25, ministries, divisions, and departments utilised only 41.31% of their allocated ADP funds—the lowest 10-month expenditure rate since at least FY12, the earliest year for which data is available on the IMED website.

To meet IMF loan conditions and cover a 38% shortfall in revenue collection, the government is expected to hike VAT rates, cut exemptions, and tighten enforcement.

VAT on mobile phones, e-commerce, construction materials, and yarn is likely to rise. A 2% advance income tax (AIT) will be levied on over 150 products.

“These measures will hit lower-income groups hardest,” warned CPD’s Mustafizur Rahman, while talking to a media outlet. “Indirect taxes are regressive.” Attempts to expand direct taxation have stalled amid bureaucratic pushback and lack of political will.

External strains

Bangladesh’s foreign debt servicing rose 25% in FY25 to $3.5 billion, while loan disbursements fell by 18%. Net foreign aid has more than halved. While speaking to an English daily, economist Ashikur Rahman stressed that currency depreciation is worsening debt burdens, urging more cautious debt management.

The country’s graduation from Least Developed Country (LDC) status in December 2026 presents additional challenges. The loss of preferential trade access will expose industries to intensified global competition.

To prepare, the government is set to rationalise over 500 tariff lines and reduce supplementary duties in line with WTO norms. However, these adjustments are being offset by expanded VAT and AIT layers.

“This is a double blow for manufacturers,” said Khorshed Alam of Little Star Spinning Mills, while speaking to an English daily. “We’re already crippled by gas shortages. Now taxes are rising too. The sector is at risk of collapse.”

Sadiq Ahmed called for investment in logistics, ports, and workforce development to support export diversification and post-LDC competitiveness.

A budget for stabilisation, not ambition

Most economists agree: the FY26 budget must be pragmatic. Without electoral legitimacy or fiscal leeway, the interim administration’s priority should be stabilisation—not populism.

Coordinated inflation control, improved tax compliance, SME-focused job creation, and rationalised spending are critical. Structural reforms in banking, energy, and public administration must not be delayed.

While addressing a recent programme, Debapriya Bhattacharya said, “Introduce a ‘corruption tax’ by recovering proceeds from past graft, loan defaults, and money laundering. That revenue can fund social protection and reduce the fiscal deficit.”

In a year of extraordinary challenges, what Bangladesh needs most is not lofty ambition—but credibility, clarity, and course correction.