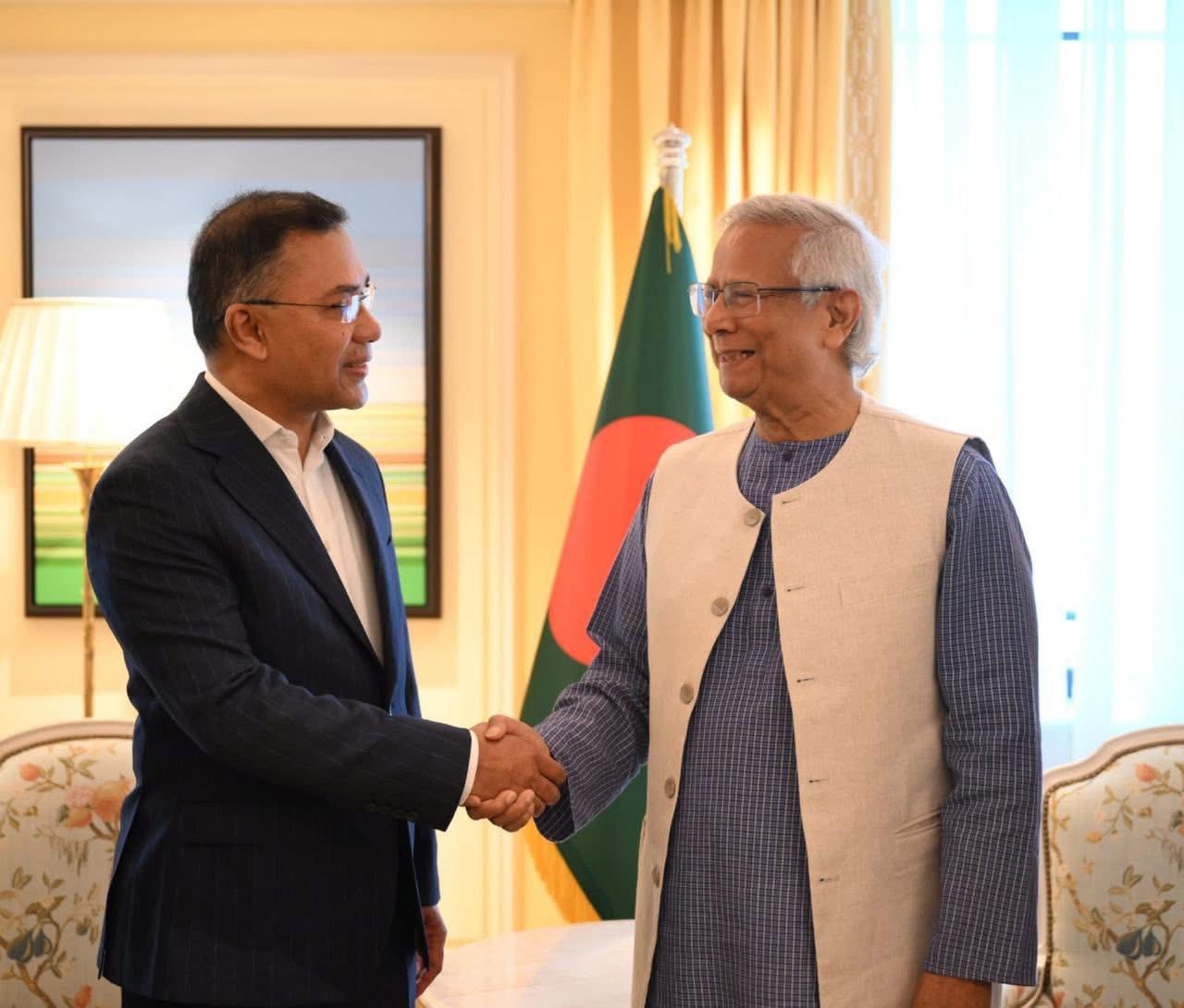

The aftermath of the Yunus-Tarique meeting in London sent tremors across the political landscape of Bangladesh. While the event was framed by many as a breakthrough, setting the stage for a national election in early February 2026, the reaction from the National Citizen Party (NCP) was far from celebratory.

For a party born out of the civic uprising that forced Sheikh Hasina from power in August, 2024, the London understanding appears to them not as a triumph of dialogue but as a troubling return to the old political script.

NCP leaders have voiced frustration over what they perceive as a closed-door arrangement between Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus and Tarique Rahman, acting chairman of the BNP. They argue that the meeting failed to reflect the democratic aspirations of the millions who marched in the streets demanding not just regime change, but a reimagining of the political order itself.

Nasiruddin Patwary, the NCP convener, warned that “deciding the future of this republic in a hotel suite without civic forces at the table betrays the very spirit of the movement.”

His remarks echo the view among many NCP activists that the London pact could mark the re-emergence of the same bipartisan deadlock that plagued Bangladesh for decades.

The core of NCP’s discomfort lies in its exclusion from what is effectively being treated as a new electoral consensus.

While BNP leaders have embraced the February timeline citing logistical advantages and the need to avoid Ramadan, NCP leaders insist that the focus must remain on completing essential reforms and trial of Sheikh Hasina and others of the past regime before any vote is held.

They fear that a rushed election could whitewash unresolved accountability issues and institutional restructuring, especially concerning the reconstitution of the Election Commission, campaign financing laws, and the depoliticisation of law enforcement agencies.

The NCP, which has been trying to gain traction among young urban voters, university networks, and reformist segments of the civil service, now finds itself outside the main dialogue shaping the country’s transitional architecture.

Dr. Yunus, for his part, has signalled that the election timeline remains conditional upon continued progress in judicial proceedings and institutional reforms. But NCP leaders remain unconvinced. They point out that merely anchoring the vote to a tentative reform schedule, without binding commitments or inclusive mechanisms, undermines the credibility of the process.

Some within the party are even contemplating symbolic protest or non-cooperation if a broader political dialogue is not initiated soon.

In this climate, the Yunus-Tarique meeting, rather than ending uncertainty, may have introduced a new layer of political tension. By narrowing the field of negotiation, it risks alienating precisely those constituencies that mobilised for democratic change in the first place.