From mafia prosecutions in New York to crimes against humanity trials in Dhaka, the fate of high-stakes criminal cases has often turned on one figure: the approver.

These insider witnesses, once complicit in crimes, agree to testify for the prosecution, sometimes in exchange for leniency, sometimes out of remorse. Their accounts, often challenged but occasionally transformative, have helped break through hardened walls of silence and bring perpetrators to justice.

In Bangladesh, the most compelling example of such a figure came in the trial of Muhammad Kamaruzzaman, a senior Jamaat-e-Islami leader, tried and convicted by the International Crimes Tribunal for crimes against humanity during the 1971 Liberation War.

Kamaruzzaman was found responsible for the Sohagpur massacre, where more than 120 unarmed villagers were slaughtered in Sherpur. The decisive witness in the case was Shahjahan Miah, a former member of the Al-Badr paramilitary force, who not only admitted his own involvement in the killings but also directly implicated Kamaruzzaman.

Shahjahan described in detail how Kamaruzzaman, as a local organiser of Al-Badr, led, supervised and instructed the massacre, personally selecting targets and coordinating with the Pakistan Army. His testimony, given in open court, was corroborated by other local witnesses and historical records.

While the defence tried to portray Shahjahan as a self-serving liar, the tribunal found his evidence credible, noting that his insider perspective helped connect the command structure to the crimes on the ground.

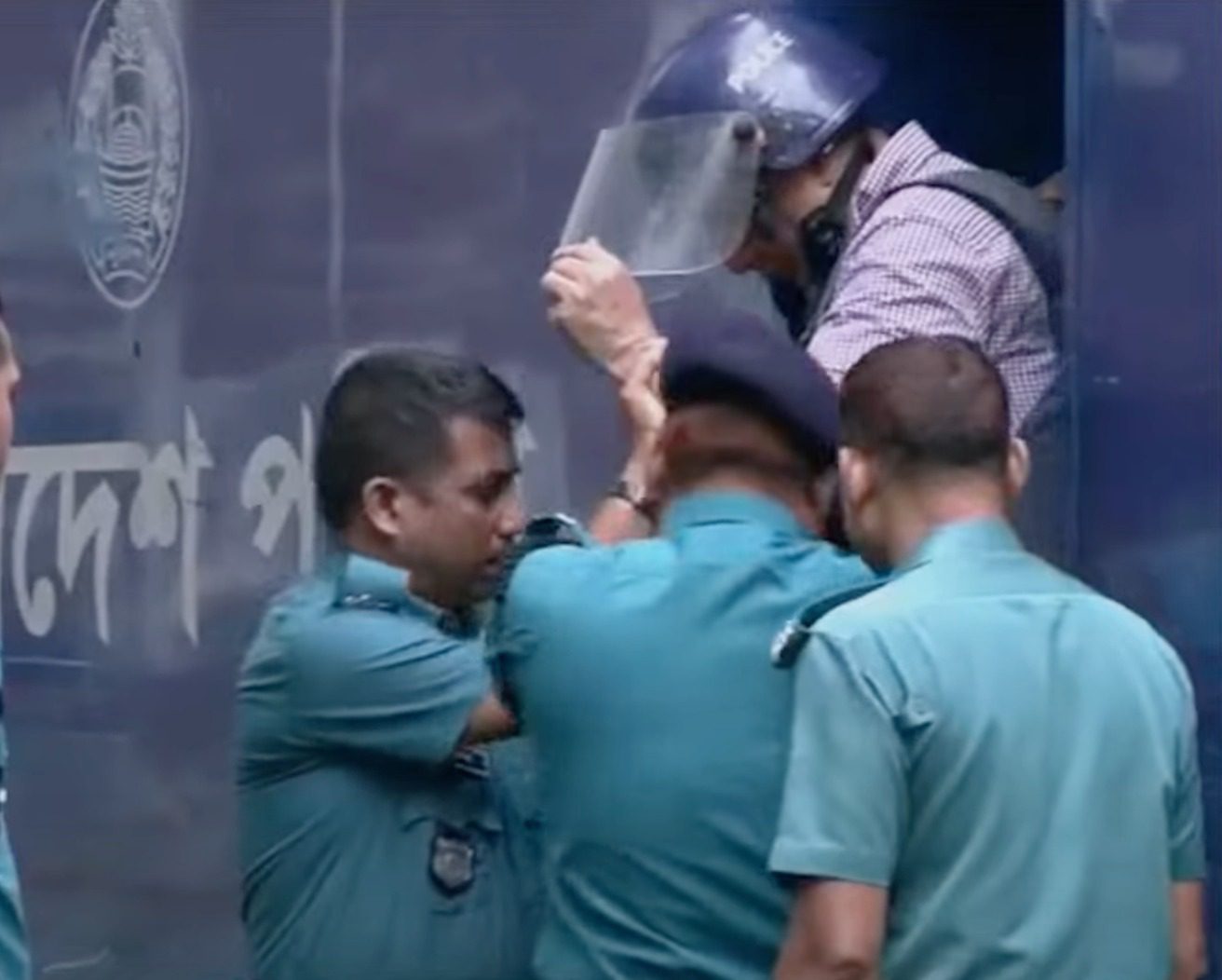

This legal provision has come under renewed focus following reports that former Inspector General of Police (IGP) Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun, now accused of crimes against humanity in connection with the July–August 2024 crackdown, has expressed his desire to become an approver.

India’s criminal justice system provides a more formal legal framework for approvers, with their testimonies often playing decisive roles in complex cases.

In the 1993 Bombay bomb blasts, multiple accused turned approvers under Section 306 of the Criminal Procedure Code, offering insider revelations that laid bare the entire terror conspiracy. Indian courts, while accepting such testimony as admissible, have consistently emphasised that it must be independently corroborated. The same caution applied in the trials following Indira Gandhi’s assassination, where insider testimony clarified motive and organisational complicity.

In Pakistan, the use of approvers has been particularly fraught, especially under authoritarian regimes.

During General Zia-ul-Haq’s rule, approvers were frequently used in political trials, often following confessions allegedly extracted through torture or coercion. The infamous 1951 Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case saw several military officers turn state witnesses, whose testimonies were instrumental in convicting figures like poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Major General Akbar Khan.

Globally, the power and peril of approvers is also evident.

In the United States, federal prosecutors have long used plea bargains to flip mobsters and drug lords. The case of Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, who testified against mafia boss John Gotti, remains iconic.

Italy’s war on organised crime followed a similar trajectory, where Tommaso Buscetta, a former mafioso, testified in the Maxi Trial, exposing the Sicilian mafia’s hierarchy and helping convict hundreds.

In Colombia, former paramilitary leaders confessed to large-scale atrocities under the country’s “Justice and Peace” law, securing lighter sentences in exchange for full disclosure. While the confessions helped recover bodies and identify massacre sites, they also stirred ethical debates about impunity.