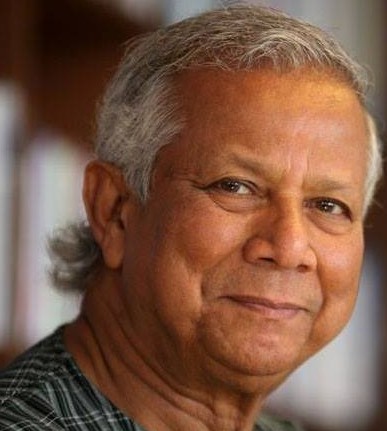

A year after the mass student-led uprising that swept Sheikh Hasina from power, Bangladesh’s interim leader Professor Muhammad Yunus has warned that the public still views government as a “permanent enemy”—a result of decades of unchecked corruption and systemic collapse.

In an exclusive interview with The Guardian, the visiting Nobel Peace Prize laureate painted a grim picture of the country’s broken institutions and outlined an urgent roadmap for political and economic reform before the April 2026 general election. “People see government as a powerful enemy,” Yunus said. “You have to live your life fighting this enemy. Somebody is always waiting to grab an enormous amount of money.”

The former microcredit pioneer, who assumed office after the July 2024 uprising against the quota system and economic mismanagement, said corruption had hollowed out governance to such an extent that basic services—such as obtaining passports or business permits—had become transactional rackets.

Yunus described the state of affairs he inherited as a “devastated economy” and “collapsed administration,” with banks issuing loans that were never meant to be repaid—essentially “gifts” to politically connected elites.

He argued that meaningful recovery requires consensus on fundamental reforms. “This is not about doing a little better. These are structural overhauls,” he said.

To that end, the interim administration formed a series of national reform commissions, which submitted recommendations in January on elections, corruption, and welfare. These have since become the basis of the proposed July Charter, a political agreement Yunus hopes to finalise by next month, ahead of the protest anniversary.

“It will be a historical document to bring all these people together,” Yunus said.

Despite optimism, Yunus acknowledged political resistance—most notably from the BNP, now the country’s most dominant force. The party has opposed proposed two-term limits for prime ministers and is pushing for an earlier election. Still, Yunus said he was “encouraged” by the unprecedented dialogue between bitter political rivals, which he sees as a foundation for long-term reform. “This country never had a culture of consensus,” he remarked.

Looking beyond politics, Yunus laid out a vision of a transformed state that serves citizens through social business, especially in healthcare and microfinance. He proposed a national microfinance banking system that would empower the poor without reliance on exploitative lenders.

Defending the microcredit model he once championed, Yunus pushed back against criticisms of high interest rates. “There is nothing wrong with microcredit,” he said. “It was given a bad name—but globally, it has been copied and worked.”

Responding to speculation about his political ambitions, Yunus made it clear: he will step down after the April election. “I was criticised by Awami League before, now everybody criticises me. It comes with the role,” he said. “In April, we will have an elected government—and then we’ll disappear.”

The interview reflects the enormous stakes facing Bangladesh’s fragile democracy. As the anniversary of last year’s uprising nears, Yunus is betting on one last political experiment: a national consensus to birth a reformed republic. Whether the July Charter becomes that instrument remains the critical test.